WalkYourTalk Interviews Artists who make the Difference: RICHARD CHEN SEE

Merit: the determining factor in leadership and art making!

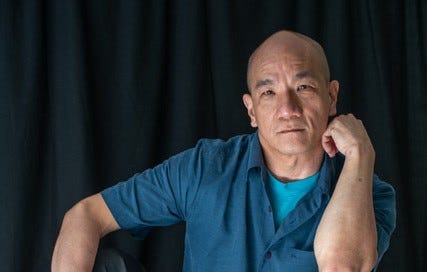

Without searching for fame, consider Richard Chen See as the quiet star of the Paul Taylor’s Dance Company in New York City, an eclectic, athletic and esteemed performer at ease in ballet and modern dance, serving this legendary company and staging the master’s work, we first met at RAMBERT, the UK’s leading modern dance company in London. With a remarkable thirty-year performance career, front-page news was never his goal, but integrity & merit is written all over this outstanding artist, dancer, human and a dear friend. Teaching ballet or modern dance, staging the Taylor repertoire in many of the world class companies, he also runs a seasonal Kayak business, including programs to inspire, at outdoor activities, the physically and economically disadvantaged. Richard, since 2021 the Director of Licensing in the administrative management of Paul’s company speaks highly of his mentor and art in this interview, a short comforting homage to another great dancer, Christopher Gable.

WalkYourTalk: You had a great career as a dancer with an early interest in teaching. I remember you as a guest at Rambert; it was striking to me then that a modern dancer was so precise with the ballet technique. Why did you really want to teach, and how is it linked to your own research as a professional dancer?

Richard: We met for the first time that day I took your class at Rambert! I was there to stage Paul Taylor’s “Roses” on the company, and I have always found it easier to warm up by taking someone else’s class over going through my own paces. LOL. Believe it or not, that was about fifteen years ago. I have the great fortune of having been rigorously trained in ballet, modern and Afro-Caribbean dance forms from a young age. I imagine that it was this range of disciplines, and hugely disparate approaches to achieving their aesthetic and technical goals, which caught my interest in learning. Ultimately, understanding how I learned to use my singular body in many different ways, made me imagine that the components of human movement had to have something in common. To paraphrase one of my early Afro-Caribbean teachers, Lavinia Williams, if you are in a ballet class, you are a ballet dancer, if you are in a modern class, you are a modern dancer… and likewise for any dance discipline in which you find yourself. So how does that work? I enjoy teaching as a means to help dancers discover that mastering their own body gives them choices about how, and what, they choose to dance! In the end, whether I am teaching ballet or another discipline, it is about getting people (whether they are professional dancers or not) to understand how their bodies can achieve the expectations of a discipline, or sport, or just everyday functioning. (below Richard rehearsing Kurt Jooss’ Green Table with his daughter Anna Markard, Oakland Ballet-courtesy OBC- archives-Photo Jump by F. Herault)

WalkYourTalk: When did you realize there was more than only dance in your life and who influenced you most; colleagues, teachers, and choreographers?

Richard: Some dancers enjoy an injury-free life as both a student and a professional dancer. Mine was not quite the case. I will not say that I was injury prone, but I loved to work hard and push my limits. The result of my approach was that I had a variety of injuries, and still I had a thirty-year performing career. Each injury was a learning process of how to both identify my technical weaknesses and the limits of my body. Learning the Art of dancing was learning how to transcend such weaknesses or limits.

When he was just returning to the world of ballet, I met Christopher Gable, the former Royal Ballet star who famously partnered Lynn Seymour to create “Romeo and Juliet” with Kenneth McMillan. With his spouse Carole, he founded the Central School of Ballet in London and later became the artistic director of Northern Ballet Theater in Leeds. However, Christopher was kind and generous enough to take an interest in my dancing and my approach to ballet training for most of my years in England training at Northern Ballet School in Manchester, and as an apprentice with Northern Ballet Theater when it was still in Manchester. I could go on and on with many stories of all that I learned from Christopher as my coach. Maybe the most lasting thing was to be aware of how dance is a language that can communicate feelings and emotions that go beyond the limits of spoken languages. Christopher had many reasons for stepping away from ballet and pursuing an acting career, and his telling of those reasons shifted with the perspective of why he was telling it. But storytelling seemed to be at the heart of his love of performing as a dancer, and the rigor and clarity of using ballet technique paralleled that of diction, rhythm, breath, and phrasing in spoken scripts. My favorite memories of Christopher grew in deep conversation outside and around the studio. The work in the studio was to understand how even the smallest look or gesture could be imbued with meaning, if the dancer is aware!

As a ballet dancer, most of my early career repertoire of dances were created in the late 19th and early 20th century and performed by generations of dancers with no direct connection to the choreographers or the originators of the roles. One of my first chances to work on an iconic work was in the role of the Profiteer in “The Green Table” (Oakland Ballet), Staged by the choreographer Kurt Jooss’ daughter, Anna Markard, her approach, and diligence marked my own when staging dances to this day. While learning a work, the dancers learn the steps, musicality, intent, context and even the evolution of every movement directly from the regisseur! There is great benefit to learning from video or film of other dancers, but finding a role, much less a phrase or even a gesture for yourself, without trying to imitate a moving image will always give the dancer more ownership of being themselves within choreography. Additionally, the style, musicality, and movement texture of individuals responding to learning a step from a living person can be more easily coached so that the dancer can achieve their best as themselves. This is not to say that adhering to the rigor of choreography and the technical skills of dancers who originated roles is open to adaptation, simply that the execution of set movement becomes Art with understanding and intention.

To sum up my answer to your question, I have to mention Paul Taylor, as a director, who gave me opportunities where I think others would have understandably passed me. As a choreographer his creative process was never the same (though he would “steal from himself, and a few others, when he felt it appropriate), and as a mentor for his dances, with Paul (unlike with Christopher Gable), I had few conversations, mostly short and to the point. However, in the fifteen years dancing his repertoire (some dating back to 1956), I was a part of more than two dozen world premieres and Paul asked me to stage many on his second company, Taylor 2, of six dancers, versus his main company of sixteen. It was somewhat of a “trial by fire.” Once I retired from performing with the main company, Paul had me continue to stage his works on conservatories and companies far and wide. We did not always but he gave me the confidence to simply know what would bring offense to his aesthetic, and let the Art breathe from there. Once upon a time, Paul’s advice to me about doing interviews was to know exactly what I did NOT want to say and let everything else fall into place.(Taylor’s Roses with Lisa Viola; photo by Lois Greenfield)

WalkYourTalk: You always seemed a nature-oriented man. Where you ever interested in “healing arts” like in movement work but also homeopathy or other alternative ways?

Richard: The short answer is, not really. However, if I were injured, there was nothing that I would not pursue to figure out how to get back to where I had been before being injured. You could say that I “dabbled” in many different approaches and learned to “listen” more carefully to my body. As a part of my recovery from a serious injury to my right leg, I started kayaking and here everything is outdoors, in nature. The liquid surface on which one kayak is a partner in constant motion, yet Mother Nature keeps that motion consistent with the laws of physics, gravity, and hydrodynamics! Becoming a professional kayak guide and instructor taught me a lot about “balance” in life and thinking about everything from a more holistic approach. My dancer’s life was indoors dark theaters/studios with artificial light, kayaking life during daylight hours, volume of moving water or tides, and atmospheric weather. Fortunately, here there is not much gradation of being “wet,” so limiting weather was more in the form of high winds, lightning storms, and no shade from overhead trees in the middle of a river or on the ocean. The balance in my life was now spending time outdoors and indoors, trusting Western medicine and believing in Eastern healing modalities, relying on my technical skills, and trusting my improvisational abilities, and just understanding that there is always another perspective to consider while taking a step forward. My greatest failing in finding balance has been in my diet, I have a pretty aggressive “sweet tooth.”

WalkYourTalk: Is there more for you than the technique and style when you teach the Paul Taylor (or other) students, and what other aspects would you introduce in a dance class? Psychology is now more and more in vogue but from many a teacher is still in its baby-shoes or simply rejected. How do you feel about the deeper approach towards a student?

Richard: My approach is clearly rooted in my background and experience. I am a firm believer in teaching what I know. Having said that, I have also spent a good portion of my life teaching kayaking to “weekend warriors” who range from people with varying physical disabilities to pro athletes. If I start from a point of empathy, where the dancers in class cannot know how dancing feels in MY body, then it is for me to guide as best I can by clearly explaining, demonstrating, encouraging, and recognizing what might best aid the dancers’/students’ learning. My hope is that classes, rehearsals, and performances can be a safe and separate space from the rest of the dancers’ lives. If every class was a performance, then any audience observing should be able to focus on the Art of dance in the room, and not the personal concerns of the performers. For me, class was always a refuge from my day-to-day concerns where for an hour and a half or two hours, I would be very focused on what I was doing at the moment. If the rest of my life could not wait for me to finish class, then I should have chosen not to take class.

As a teacher, it can be hard to escape the dynamic of dancers in distress elsewhere in their lives. However, I prefer to be available for consultation outside of class and offer individuals my perspectives on how and when to take class, so that it can truly be a communal activity. Dance is most joyfully practiced in the company of others where accomplishments can be shared, and support from fellow dancers can be invigorating.

Hopefully, my teaching “style” does not offend anyone, but I also know I will not be everyone’s favorite teacher. The essence of my teaching is “problem solving” physical tasks and rhythm, there is no singular method for achieving a movement skill. Nor is everyone naturally musical. And the aesthetics of line and form should be coached for each body. Just as we talk about teachers needing to be open to change and new approaches, so do students need to be open to learning from their knowledge and experience. To be skilled takes focus, time, and consistent practice.

WalkYourTalk: How do you see the present evolution in ballet, teaching & the new generation reacting quite differently compared to even last century and are there new approaches? What is the essence of this Art form to you?

Richard: I am not entirely sure that I am equipped to answer such a global question. And this may stem from my origins in becoming a professional dancer. I am from a generation where before you could be accepted into ballet, you were openly assessed for your proportions, potential physical facility, ability to discern rhythm, origin of birth, and racial ancestry. Once you got past those gates, still nothing was guaranteed. Out of my story came a perspective that if I did not see someone like me in class or on stage, then it was a perfect opportunity to “fill the void.” As a minority in the western world where I have lived my whole life, I always knew that I would likely be subject to “quotas” and there would always be a tipping point where there would not be room for one more.

Racially, I am of Chinese descent, and ethnically, I am a second-generation West Indian born, raised on the island of Jamaica. Finding my way into, and sustaining, a career in dance was not written in any books I read. I look Chinese, I speak English with a Jamaican “lilt,” and I move expansively like I belong on a sports field. Yet, as you described at the beginning of this interview, I was often noted for my technical precision and musical clarity as a dancer. After dancing in England for a few years, my Jamaican passport expired, and I eventually ended up in the USA. By US standards. I am not tall, and I look Asian, but I found that if my dancing were good enough, it could supersede these two factors. However, in combination with my Jamaican accent, the best range of performance opportunities for me would be in dance, as non-traditional casting was more readily seen. If the dancer appeared to have effortless technique, inherent musicality, and convincing non-verbal acting, they might be cast in any role in a ballet. I do not see striving to excel in these attributes as anything less than what every dancer hopes to achieve. And I never felt entitled to be given an opportunity just because I was as good as the next dancer. I wanted to win my position or role because I was the best. Without claiming to have been the best, I learned to embrace my competitiveness, which made me the best dancer, and my toughest competitor was myself! The essence of dance as an Art form is its ability to communicate and illustrate the human imagination and condition without words across cultures. And to do this, dancers need to be physically articulate and the best that they can be individually; that is how I feel. (with Paul Taylor, @Paris Opera Ballet)

WalkYourTalk: I always experienced you as outspoken, is this a quality that took a lot of time to develop? The ballet world used to be a domain that belonged to the ballerina, but the leadership was mostly male. Many have a feeling that now everything goes, the media often claim gender seems more important than merit. Your thoughts?

Richard: Hmmm. I always had a sense that words and actions have consequences, and that if I felt it necessary to speak out about something that I wanted to be prepared to accept the consequences. It is easy as a young dancer to stay silent rather than risk losing a job, or a role, or accept being blamed for something beyond your control (like an accidental injury, or even your proportions) Dancers are trained to “do” not to speak. Yet in high school, I took Rhetoric as a standard course, which was all about using language to present a statement and then to support/oppose the statement with well-reasoned argument. At first, I used to think that dancers lived in a world separate from one where you could defend your thoughts and convictions. Then, as I was struggling to recover from an injury, I found myself over-working and prolonging my rehabilitation as a result. A fellow dancer offered me sage advice pointing out I was taking out my frustration with the injury on myself, rather than addressing the injury directly and acting accordingly. In an obtuse way, he also pointed out that there was little benefit in making myself sick over being angry at people when the targets of my anger had no idea how I was feeling. Maybe connecting with others who might be able to affect change could benefit everyone, and I might not build up quite as much frustration in my life.

So, you are right to think of me as “outspoken,” and I will add that I rarely say things where I have not considered the possible outcomes, and I am prepared to accept the consequences.

To answer your specific question, I maintain that “merit” should be the determining factor in leadership and art making. Statistics alone do not tell the whole story, and the USA has a long history of “affirmative action” where, as I mentioned earlier, I might well have been a number in a percentage quota of how many males, how many non-white, how many Asians, etc. and on down the line. I did not grow up with the privilege of rigorous training in ballet as a young child, but I did have a career where “merit” allowed my excellence to provide me with opportunity that people today try to tell me was not available in my time. I may have had to fight a little harder than some to earn my positions, but I am nonetheless proud that my accomplishments are merit-based rather than gender, race, or minority status. Ironically, if my “identification” does provide me access to opportunity, I am not above exploring the option, but I do not want it at the expense of a better artist than me. Their excellence might be something from which I can learn and further my Artistic life and endeavors.

WalkYourTalk: As a sports man does it make you feel different, closer to an authentic self in today’s AI-oriented society?

Richard: Canoeing (kayaking specifically to me, in US vernacular) was an avocation to which I was introduced on account of a dance injury, as I described earlier. It definitely added a counterpoint to my theatre life and consistently brought me joy. The physical balance and control I learned from dancing applies directly to my comfort with paddling kayaks, canoes, and even stand-up paddle boards (SUPs). My experience with contact improvisation coincided with my early paddling career and the water is an incredibly dynamic partner! I draw myriad connections between my outdoor and indoor lives, and as I mentioned earlier, “balance” reminds us that there is always a different way to look at life, and one is not necessarily better than the other.

WalkYourTalk: The world is taking a serious turn in consciousness and more and more people are waking up to their own higher understanding of the realities we have lived in for so many centuries. Your advice in this regard?

Richard: If I understand your question correctly, I think my response would be more along the lines of encouraging people to continually question and investigate their perspectives on life. I find it easier to know if I disagree with the world around me once I have decided on my own perspective. And if my investigation proves me wrong in one moment, then I need to be open to at least accepting that truth, even if I do not change course immediately.

WalkYourTalk: There are still many people who do not really care about moving out of the old paradigm. In the artist’s world a great % still prefers the old ways. When so, how do you react and how do you see an individual’s life change while broadening her/his horizon?

Richard:: I can understand not wanting to “move out of an old paradigm,” as we might feel that we excelled and progressed under that paradigm. My life as a regisseur and teacher has been to always question my approach, and to hopefully get some clues about moving forward from the dancers’ responses to my directions/coaching/teaching. The additional question I ask both myself and the directors I work with is “why”? Why that particular dance? Why this particular course? I may start out with one answer and find a different one along the way. That is okay with me. I think that human nature and our bodies have not evolved as fast as our collective knowledge of science, medicine, engineering, and all of our human-caused advances. The trick is to learn what we can from the paradigms we grew up with and see if we really can do better. The investigation alone will change us for the better! (in Taylor’s masterpiece Aureole-Photo by Jack Mitchell)

WalkYourTalk: You are a freelance artist with much freedom, is there anything you would really like to change or experience you have not yet?

Richard: I guess that it has been a while since we have had a chance to visit, but in 2021 the Paul Taylor Dance Foundation invited me to collaborate with them full-time to form an in-house licensing division for the management and staging of Paul Taylor’s dances. I admit that I seem to have consistently jumped between being a free-lance artist and a full-time employee of a single organization throughout my life. Paul Taylor died in 2018, and I have been staging his dances on companies and conservatories since 1999 as a free-lance artist. It seems serendipitous to have had a fifteen-year career as a dancer for Paul Taylor, and then to have had the opportunity to stage his dances when I could still get feedback from him about the dances. I also had the fortune of having started to stage his works while I was still performing them, providing me with that dual perspective of what it feels like to dance, and what the dancing looks like from the audience.

I am in the midst of something that is expanding my life experience and utilizing so much of what I have learned before, at, and beyond Paul Taylor. In forming the licensing division to care for Taylor’s dances, I have opted to build “histories” of the dances which I am licensing to outside organizations to perform. This process is painstaking and rewarding as I get to know the dances from the many iterations they have had with revivals within the company, and how they play when staged by different dancers. My objective is not to set a definitive version of any dance, but to allow an access to variants (good and bad) which provides them with a more well-rounded perspective on each role and the dance as a whole. Costumes, lighting, music all have to be documented and collated into dance specific collections of information that also includes an “origin” story based on interviews with original cast members, and maybe a few on whom major changes were made in later revivals. I do not get to do as much staging of Taylor works, as I used to do, but I have become more intimate with the dances than ever before. I am responsible for pairing the best regisseurs with the licensing organizations and shepherding the process from contracting to final payments. Occasionally the current Artistic Director, Michael Novak asks me to help with reconstructions of Taylor dances for the current dancers! And once again my life experience has a chance to dance in a studio!

WalkYourTalk: Do you have any further thoughts you would like to share for the dancers and non-dancers? Richard: Dear Luc! You have carefully curated challenging, insightful questions for me to answer. You have asked me to join you on this platform, alongside luminaries whom I have always admired, and who inspired my own career in different ways. I am deeply appreciative of being considered by you as a worthy interview. I believe to have offered what I might think of as wisdom at this time, in answering your questions. Christopher used to always encourage me to choose my next step in life carefully, to make a choice, and do not be afraid to make a change as the very next choice. WalkYourTalk: Thank you for answering our questions in such an inspiring manner! Wishing you great success with your own daily endeavors. (Below Christopher Gable-Archives)